Yield surface

A yield surface is a five-dimensional surface in the six-dimensional space of stresses. The yield surface is usually convex and the state of stress of inside the yield surface is elastic. When the stress state lies on the surface the material is said to have reached its yield point and the material is said to have become plastic. Further deformation of the material causes the stress state to remain on the yield surface, even though the shape and size the surface may change as the plastic deformation evolves. This is because stress states that lie outside the yield surface are non-permissible in rate-independent plasticity, though not in some models of viscoplasticity.[1]

The yield surface is usually expressed in terms of (and visualized in) a three-dimensional principal stress space ( ), a two- or three-dimensional space spanned by stress invariants (

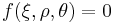

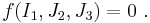

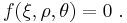

), a two- or three-dimensional space spanned by stress invariants ( ) or a version of the three-dimensional Haigh–Westergaard stress space. Thus we may write the equation of the yield surface (that is, the yield function) in the forms:

) or a version of the three-dimensional Haigh–Westergaard stress space. Thus we may write the equation of the yield surface (that is, the yield function) in the forms:

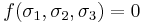

where

where  are the principal stresses.

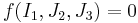

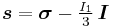

are the principal stresses. where

where  is the first principal invariant of the Cauchy stress and

is the first principal invariant of the Cauchy stress and  are the second and third principal invariants of the deviatoric part of the Cauchy stress.

are the second and third principal invariants of the deviatoric part of the Cauchy stress. where

where  are scaled versions of

are scaled versions of  and

and  and

and  is a function of

is a function of  .

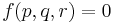

. where

where  are scaled versions of

are scaled versions of  and

and  , and

, and  is the Lode angle.

is the Lode angle.

Contents |

Invariants used to describe yield surfaces

The first principal invariant ( ) of the Cauchy stress (

) of the Cauchy stress ( ), and the second and third principal invariants (

), and the second and third principal invariants ( ) of the deviatoric part (

) of the deviatoric part ( ) of the Cauchy stress are defined as:

) of the Cauchy stress are defined as:

where ( ) are the principal values of

) are the principal values of  , (

, ( ) are the principal values of

) are the principal values of  , and

, and

where  is the identity matrix.

is the identity matrix.

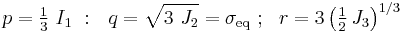

A related set of quantities, ( ), are usually used to describe yield surfaces for cohesive frictional materials such as rocks, soils, and ceramics. These are defined as

), are usually used to describe yield surfaces for cohesive frictional materials such as rocks, soils, and ceramics. These are defined as

where  is the equivalent stress. However, the possibility of negative values of

is the equivalent stress. However, the possibility of negative values of  and the resulting imaginary

and the resulting imaginary  makes the use of these quantities problematic in practice.

makes the use of these quantities problematic in practice.

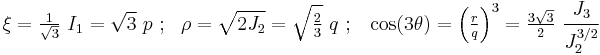

Another related set of widely used invariants is ( ) which describe a cylindrical coordinate system (the Haigh–Westergaard coordinates). These are defined as:

) which describe a cylindrical coordinate system (the Haigh–Westergaard coordinates). These are defined as:

The  plane is also called the Rendulic plane. The angle

plane is also called the Rendulic plane. The angle  is called the Lode angle[2] and the relation between

is called the Lode angle[2] and the relation between  and

and  was first given by Nayak and Zienkiewicz in 1972 [3]

was first given by Nayak and Zienkiewicz in 1972 [3]

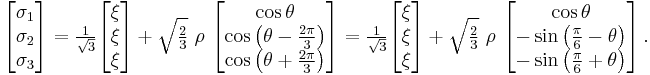

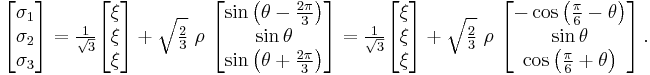

The principal stresses and the Haigh–Westergaard coordinates are related by

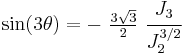

A different definition of the Lode angle can also be found in the literature:[4]

in which case

Whatever definition is chosen, the angle  varies between -30 degrees to +30 degrees.

varies between -30 degrees to +30 degrees.

Examples of yield surfaces

There are several different yield surfaces known in engineering, and those most popular are listed below.

Tresca yield surface

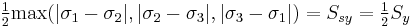

The Tresca yield criterion is taken to be the work of Henri Tresca.[5] It is also referred as also known as the maximum shear stress theory (MSST) and the Tresca–Guest (TG) criterion. In terms of the principal stresses the Tresca criterion is expressed as

Where  is the yield strength in shear, and

is the yield strength in shear, and  is the tensile yield strength.

is the tensile yield strength.

Figure 1 shows the Tresca–Guest yield surface in the three-dimensional space of principal stresses. It is a prism of six sides and having infinite length. This means that the material remains elastic when all three principal stresses are roughly equivalent (a hydrostatic pressure), no matter how much it is compressed or stretched. However, when one of principal stresses becomes smaller (or larger) than the others the material is subject to shearing. In such situations, if the shear stress reaches the yield limit then the material enters the plastic domain. Figure 2 shows the Tresca–Guest yield surface in two-dimensional stress space, it is a cross section of the prism along the  plane.

plane.

von Mises yield surface

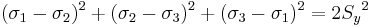

The von Mises yield criterion is expressed in the principal stresses as

where  is the yield strength in uniaxial tension.

is the yield strength in uniaxial tension.

Figure 3 shows the von Mises yield surface in the three-dimensional space of principal stresses. It is a circular cylinder of infinite length with its axis inclined at equal angles to the three principal stresses. Figure 4 shows the von Mises yield surface in two-dimensional space compared with Tresca–Guest criterion. A cross section of the von Mises cylinder on the plane of  produces the elliptical shape of the yield surface.

produces the elliptical shape of the yield surface.

Mohr–Coulomb yield surface

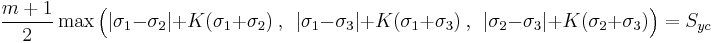

The Mohr–Coulomb yield (failure) criterion is similar to the Tresca criterion, with additional provisions for materials with different tensile and compressive yield strengths. This model is often used to model concrete, soil or granular materials. The Mohr–Coulomb yield criterion may be expressed as:

where

and the parameters  and

and  are the yield (failure) stresses of the material in uniaxial compression and tension, respectively. The formula reduces to the Tresca criterion if

are the yield (failure) stresses of the material in uniaxial compression and tension, respectively. The formula reduces to the Tresca criterion if  .

.

Figure 5 shows Mohr–Coulomb yield surface in the three-dimensional space of principal stresses. It is a conical prism and  determines the inclination angle of conical surface. Figure 6 shows Mohr–Coulomb yield surface in two-dimensional stress space. It is a cross section of this conical prism on the plane of

determines the inclination angle of conical surface. Figure 6 shows Mohr–Coulomb yield surface in two-dimensional stress space. It is a cross section of this conical prism on the plane of  .

.

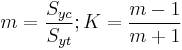

Drucker–Prager yield surface

The Drucker–Prager yield criterion is similar to the von Mises yield criterion, with provisions for handling materials with differing tensile and compressive yield strengths. This criterion is most often used for concrete where both normal and shear stresses can determine failure. The Drucker–Prager yield criterion may be expressed as

where

and  ,

,  are the uniaxial yield stresses in compression and tension respectively. The formula reduces to the von Mises equation if

are the uniaxial yield stresses in compression and tension respectively. The formula reduces to the von Mises equation if  .

.

Figure 7 shows Drucker–Prager yield surface in the three-dimensional space of principal stresses. It is a regular cone. Figure 8 shows Drucker–Prager yield surface in two-dimensional space. The ellipsoidal-shaped elastic domain is a cross section of the cone on the plane of  ; here it is shown enclosing the elastic domain for the Mohr–Coulomb yield criterion, although the converse scenario is also possible.

; here it is shown enclosing the elastic domain for the Mohr–Coulomb yield criterion, although the converse scenario is also possible.

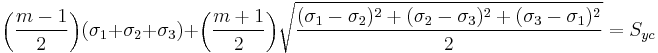

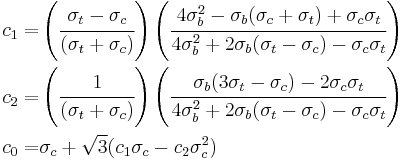

Bresler–Pister yield surface

The Bresler–Pister yield criterion is an extension of the Drucker Prager yield criterion that uses three parameters, and has additional terms for materials that yield under hydrostatic compression. In terms of the principal stresses, this yield criterion may be expressed as

where  are material constants. The additional parameter

are material constants. The additional parameter  gives the yield surface an ellipsoidal cross section when viewed from a direction perpendicular to its axis. If

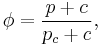

gives the yield surface an ellipsoidal cross section when viewed from a direction perpendicular to its axis. If  is the yield stress in uniaxial compression,

is the yield stress in uniaxial compression,  is the yield stress in uniaxial tension, and

is the yield stress in uniaxial tension, and  is the yield stress in biaxial compression, the parameters can be expressed as

is the yield stress in biaxial compression, the parameters can be expressed as

Willam–Warnke yield surface

The Willam–Warnke yield criterion is a three-parameter smoothed version of the Mohr–Coulomb yield criterion that has similarities in form to the Drucker–Prager and Bresler–Pister yield criteria.

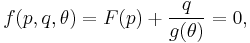

The yield criterion has the functional form

However, it is more commonly expressed in Haigh–Westergaard coordinates as

The cross-section of the surface when viewed along its axis is a smoothed triangle (unlike Mohr–Coulumb). The Willam–Warnke yield surface is convex and has unique and well defined first and second derivatives on every point of its surface. Therefore the Willam–Warnke model is computationally robust and has been used for a variety of cohesive-frictional materials.

Bigoni–Piccolroaz yield surface

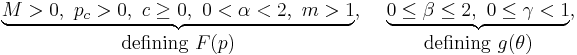

The Bigoni–Piccolroaz yield criterion [6] is a seven-parameter surface defined by

where  is the “meridian” function

is the “meridian” function

describing the pressure-sensitivity and  is the “deviatoric” fuction

is the “deviatoric” fuction

describing the Lode-dependence of yielding. The seven, non-negative material parameters:

define the shape of the meridian and deviatoric sections.

This criterion represents a smooth and convex surface, which is closed both in hydrostatic tension and compression and has a drop-like shape, particularly suited to describe frictional and granular materials. This criterion has also been generalized to the case of surfaces with corners.[7]

-plane

-planeReferences

- ^ Simo, J. C. and Hughes, T,. J. R., (1998), Computational Plasticity, Spinger.

- ^ Lode, W. (1926). Versuche über den Einfuss der mittleren Hauptspannung auf das Fliessen der Metalle Eisen Kupfer und Nickel. Zeitung Phys., vol. 36, pp. 913–939.

- ^ Nayak, G. C. and Zienkiewicz, O.C. (1972). Convenient forms of stress invariants for plasticity. Proceedings of the ASCE Journal of the Structural Division, vol. 98, no. ST4, pp. 949–954.

- ^ Chakrabarty, J., 2006, Theory of Plasticity: Third edition, Elsevier, Amsterdam.

- ^ Tresca, H. (1864). Mémoire sur l'écoulement des corps solides soumis à de fortes pressions. C.R. Acad. Sci. Paris, vol. 59, p. 754.

- ^ Bigoni, D. and Piccolroaz, A., (2004), Yield criteria for quasibrittle and frictional materials, International Journal of Solids and Structures 41, 2855-2878.

- ^ Piccolroaz, A. and Bigoni, D. (2009), Yield criteria for quasibrittle and frictional materials: a generalization to surfaces with corners, International Journal of Solids and Structures 46, 3587-3596.

![\begin{align}

I_1 & = \text{Tr}(\boldsymbol{\sigma}) = \sigma_1 %2B \sigma_2 %2B \sigma_3 \\

J_2 & = \tfrac{1}{2} \boldsymbol{s}:\boldsymbol{s} =

\tfrac{1}{6}\left[(\sigma_1-\sigma_2)^2%2B(\sigma_2-\sigma_3)^2%2B(\sigma_3-\sigma_1)^2\right] \\

J_3 & = \det(\boldsymbol{s}) = \tfrac{1}{3} (\boldsymbol{s}\cdot\boldsymbol{s}):\boldsymbol{s}

= s_1 s_2 s_3

\end{align}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/1f13e97d75aaa5a184b83bc23d38e02d.png)

![S_{yc} = \tfrac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\left[(\sigma_1-\sigma_2)^2%2B(\sigma_2-\sigma_3)^2%2B(\sigma_3-\sigma_1)^2\right]^{1/2} - c_0 - c_1~(\sigma_1%2B\sigma_2%2B\sigma_3) - c_2~(\sigma_1%2B\sigma_2%2B\sigma_3)^2](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/0f7de60e49d4763163410775aedbed14.png)

![F(p) =

\left\{

\begin{array}{ll}

-M p_c \sqrt{(\phi - \phi^m)[2(1 - \alpha)\phi %2B \alpha]}, & \phi \in [0,1], \\

%2B\infty, & \phi \notin [0,1],

\end{array}

\right.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/546b984534351d26ab75b7f8ab2ffb4c.png)

![g(\theta) = \frac{1}{\cos[\beta \frac{\pi}{6} - \frac{1}{3} \cos^{-1}(\gamma \cos 3\theta)]},](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/fb2a2b37d535ca7594884235d86f6422.png)